Selling protection through credit default swaps is akin to writing put options on sovereign default. Together with tenuous market liquidity, this explains the negative skew and heavy fat tails of generic CDS (short protection or long credit) returns. Since default risk depends critically on sovereign debt dynamics, point-in-time metrics of general government debt sustainability for given market conditions are plausible trading indicators for sovereign CDS markets and do justice to the non-linearity of returns. There is strong evidence of a negative relation between increases in predicted debt ratios and concurrent returns. There is also evidence of a negative predictive relation between debt ratio changes and subsequent CDS returns. Trading these seems to produce modest but consistent alpha.

The below post is based on proprietary research of Macrosynergy.

A Jupyter notebook for audit and replication of the research results can be downloaded here. The notebook operation requires access to J.P. Morgan DataQuery to download data from JPMaQS, a premium service of quantamental indicators. J.P. Morgan offers free trials for institutional clients. Also, there is an academic research support program that sponsors data sets for relevant projects.

This post ties in with this site’s summary of macro trends and systematic trading strategies.

A few basics of sovereign CDS

“Credit default swaps [CDS] are credit protection contracts whereby one party agrees, in exchange for a periodic premium, to make a contingent payment in the case of a defined credit event. For buyers of credit protection, the CDS market offers the opportunity to reduce credit concentration and regulatory capital while maintaining customer relationships. For sellers of protection, it offers the opportunity to take credit exposure over a customized term and earn income without having to fund the position.” [BIS]

“[Sovereign] CDS are analogous to insurance: in exchange for a fee paid to the seller, they provide protection to buyers from losses that may be incurred on sovereign debt resulting from a ‘credit event.’ Credit events include failure to pay interest or principal on, and restructuring of, one or more obligations issued by the sovereign… Restructuring events include interest or principal reductions and postponements, subordination of creditor rights, and redenomination into a nonpermitted currency, and are binding on all holders of the restructured obligations.” [IMF]

“A sovereign CDS spread is the effective annual cost of the protection it provides against a credit event, expressed as a percent of the notional amount of protection. A credit spread on a government bond is the difference between its yield to maturity and that of an otherwise similar ‘riskless’ benchmark fixed-income instrument.” [IMF]

“The [sovereign CDS] premium should roughly correspond to the spread of the reference obligation of equal maturity over the risk-free rate. For this reason, we should expect the premium to show a fairly close cross-sectional relationship with the credit risk of the underlying reference asset.” [BIS]

“I present… a theory of the risk structure of interest rates. The use of the term ‘risk’ is restricted to the possible gains or losses to bondholders as a result of (unanticipated) changes in the probability of default [based on] Black and Scholes’… general equilibrium theory of option pricing… The same basic approach could be applied in developing a pricing theory for corporate liabilities in general.” [Merton]

“Government liabilities include foreign currency debt, domestic currency debt, and obligations owed by the government to the monetary authorities and the guarantees to ‘too-important-to-fail’ entities. Government assets include a claim on a portion of the foreign currency reserves held by the monetary authority and other public sector assets such as the present value of the primary fiscal surplus… Sovereign distress increases when the market value of sovereign assets declines relative to its contractual obligations on debt. Default ultimately occurs when the sovereign assets fall below the contractual liabilities… Default risk increases when the value of sovereign assets declines toward the distress barrier or when asset volatility increases such that the value of sovereign assets becomes more uncertain and the probability of the value falling below the distress barrier becomes higher.” [Li Ong]

“Measures of sovereign credit risk are correlated with the level of sovereign debt and with another measure of risk derived from an alternative structural pricing model… Market expectations regarding sovereign risk follow dynamic developments in economic fundamentals.” [ECB]

Generic sovereign CDS return data

For the empirical analysis in this post, we use generic sovereign CDS returns arising from selling protection through sovereign credit default swaps for a range of developed and emerging markets. The source is the J.P. Morgan Macrosynergy Quantamental System. In particular, we focus on daily 5-year maturity CDS sovereign returns calculated from the continuous series of CDS spreads (view documentation here).

This post looks at two versions of these returns: standard returns per USD notional and volatility-targeted returns. The latter is the protection seller’s PnL on a position that is scaled to a 10% annualized standard deviation target based on an exponential moving average of daily returns with an 11-day half-life. Positions are rebalanced at the end of each month and maximum leverage (notional to risk capital) is constrained to 25.

The post looks at sovereign CDS markets for the following developed market countries: CHF/Switzerland (since 2009), DEM/German (since 2005), ESP/Spain (since 2005), FRF/France (since 2006), GBP/UK (since 2007), ITL/Italy (since 2005), JPY/Japan (since 2001), SEK/Sweden (since 2008), USD/U.S. (since 2014).

The post looks at CDS markets for the following emerging market sovereigns: BRL/Brazil (since 2000), CLP/Chile (since 2007), CNY/China (since 2006), COP/Colombia (since 2000), CZK/Czechia (since 2004), HUF/Hungary (since 2000), IDR/Indonesia ((since 2004), ILS/Israel (2004), KRW/South Korea (since 2004), MXN/Mexico (since 2000), MYR/Malaysia (since 2003), PEN/Peru (since 2003), PHP/Philippines (since 2005), PLN/Poland (since 2000), RON/Romania (since 2002), THB/Thailand (since 2005), TRY/Turkey (since 2002), ZAR/South Africa (since 2002)

The sovereign CDS market is primarily an over-the-counter market that became reasonably liquid for some EM countries during the 2000s and for certain developed countries from the late 2000s. Compared to bond and equity markets, sovereign CDS liquidity in major contracts has remained shallower and more tenuous, however. The distribution of CDS returns across sovereigns reflects vast differences in default risk, the characteristic of short protection returns as short option returns, and fragile liquidity.

- The variance of returns has been vastly different across obligors. The standard deviation of Brazil’s 5-year CDS returns has been 37 times larger than that of Switzerland.

- Protection seller returns have been skewed towards the negative side, with an average sample skewness across all sovereigns of -1.3.

- CDS returns have been highly leptokurtic, i.e., displayed fat tails or a proclivity towards outliers from standard ranges, with a standard kurtosis measure of 90.

The proclivity to rare drawdown events shows also prominently in the timelines below. They also emphasize that the long-term return profile of a protection seller has been quite unattractive, with 16 out of 27 sovereigns earning negative long-term PnL. All sovereigns’ short-protection returns, except maybe those of Switzerland, have displayed inordinate downside volatility that looks very challenging for risk management.

Volatility targeting is a simple way of imposing some risk management on CDS positions. It naturally evens out return variance across sovereigns. However, vol-targeting increases skewness and cannot remove fat tails, as the standard kurtosis measure still averages 75 across sovereigns. Also, it further reduces the risk-adjusted PnL of protection seller positions, with 23 of 27 countries posting negative long-term returns and some showing consistent negative drifts. This plausibly reflects that vol-targeting reduces notional exposure when sovereigns move closer to default risk and the implied option is close to its strike level. However, far out-of-the-money options usually carry lower premiums compared to at-the-money options, as the value of the former is entirely composed of time value and implied volatility.

Standard debt sustainability indicators

To assess the influence of debt sustainability on sovereign CDS returns we use ‘mechanical’ general government debt sustainability metrics of JPMaQS (view documentation here). They are very simple and highly stylized but popular for rough assessments. The calculation is based on the latest information states of debt and deficit ratios and estimates of the latest local-currency real government bond yields. As such, these ratios always assume that concurrent market conditions prevail going forward and are mostly an indication of the escalation risk of changes in credit and financial market conditions. Note that the daily time series of JPMaQS are point-in-time information: they represent what the market knew about the variable at the end of the day.

The main quantamental indicator for this analysis is the “extrapolated public debt ratio”. This is an extrapolated general government debt-to-GDP ratio in 10 years, given the current primary balance, real interest rate estimate, and the concurrent general government debt ratio. It indicates where all other things equal, the debt-to-GDP ratio of a government would move, if interest rates, GDP growth, and the primary balance remained unchanged.

The below facet shows the evolution for all sovereigns with (reasonably) liquid CDS markets, except the Philippines, which lacks underlying data. Generally, these data evolve in the medium term with estimations of debt and deficit ratios. However, the short-term changes are dominated by (local-currency) real interest rates. Hence, timelines show both trends and sudden shifts and spikes.

To test various hypotheses on the relationship between mechanical sustainability indicators and CDS returns we look at short-term and medium-term trends in the information states of extrapolated general government debt ratios.

- Biweekly trend: This is the difference between the information state of the debt ratio of the latest day and the average information state of the previous two weeks (10 trading days), winsorized at 10 percentage points.

- Monthly trend: This is the difference between the information state on the debt ratio of the latest day and the average information state of the previous month (21 trading days), winsorized at 10 percentage points.

- Annual trend: This is the difference between the information state on the debt ratio of the latest week (5 trading days) and the average information state of the previous year (252 trading days), winsorized at 20 percentage points.

- Bi-annual trend: This is the difference between the information state on the debt ratio of the latest month (21 trading days) and the average information state of the previous 2 years (504 trading days), winsorized at 20 percentage points.

The purpose of winsorization is to avoid the dominance of individual episodes in the sample and to weed out data outliers.

Concurrent relation of sustainability data and CDS returns

The first simple hypothesis is that deterioration in debt sustainability indicators coincides with negative CDS returns. In particular, one would expect that an increase in the extrapolated government debt ratio increases default risk and the price for protection.

Indeed, there has been a highly significant relation between monthly extrapolated government debt ratio trends and 5-year CDS (short-protection) returns since 2000. This mainly reflects a positive relation between local-currency real interest rates and sovereign credit spreads.

This negative correlation increases dramatically if one adds all the outliers that are filtered out by standard winsorization. This high correlation relies mainly on six extreme events, however.

Short-term information advantage

The second hypothesis is that conscientiously following short-term trends in sustainability indicators offers an information advantage and predicts subsequent CDS returns. This hypothesis is based on the theory of rational inattention and highlights a specific advantage of systematic macro trading signals. In particular, short-term trends in extrapolated debt ratios are expected to predict subsequent short-protection CDS returns negatively.

Evidence of this negative short-term predictive relation is copious. It has been significant for monthly and biweekly debt ratio trends and for weekly, monthly, and quarterly subsequent returns. The negative predictive relation prevailed for both developed and emerging markets, but the evidence is far more significant for the latter. This partly reflects that emerging markets provide a richer data set with a greater number and variety of debt sustainability crises.

Accuracy of the prediction of the monthly direction of returns has been 51% for monthly debt ratio trends and 52.4% for biweekly debt ratio trends

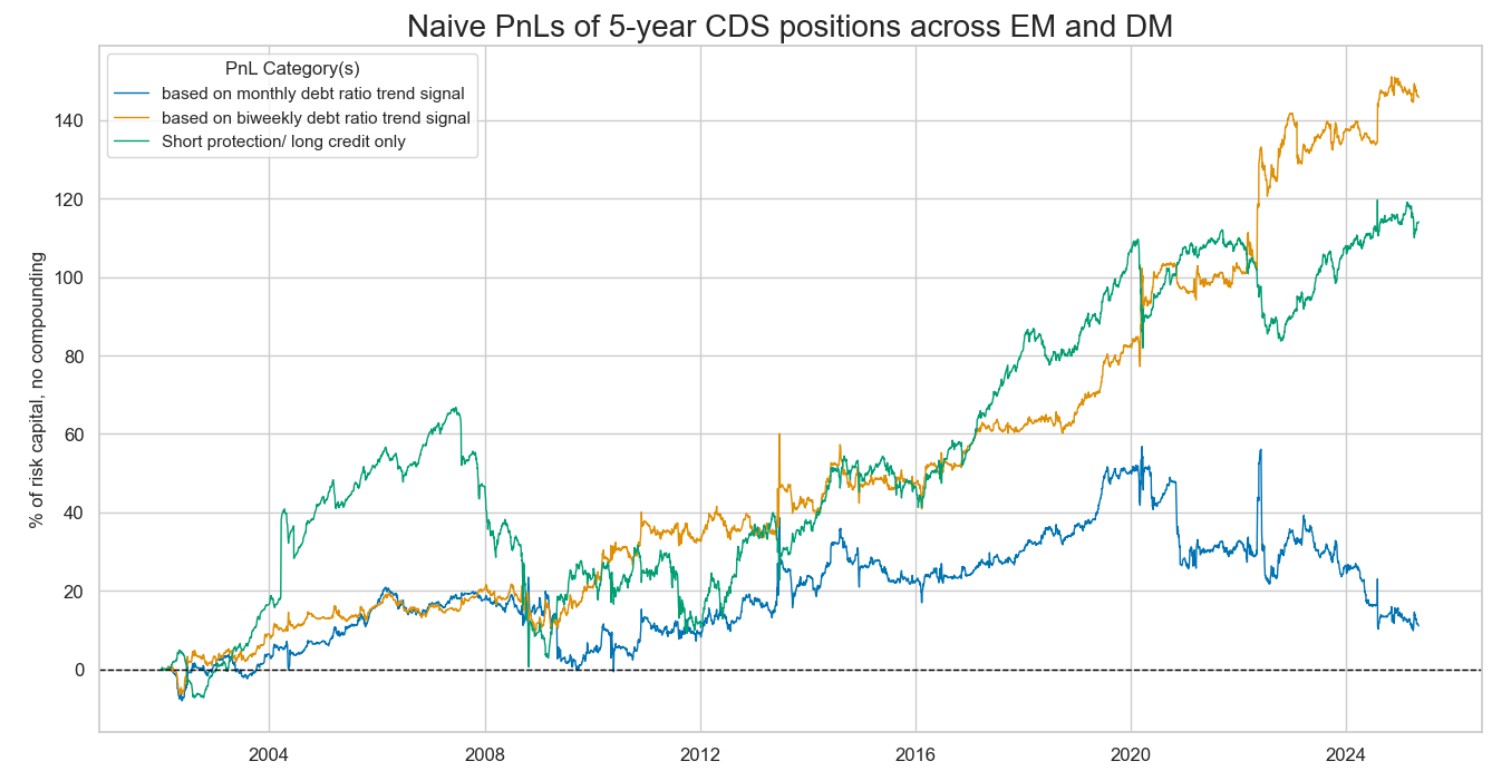

To gauge the economic value of extrapolated public debt signals, we calculate naïve PnLs based on standard rules used in Macrosynergy posts. This means that positions are calculated based on monthly normalized debt trends, i.e., z-scores around their natural zero level winsorized at 2 standard deviations. Positions are rebalanced monthly based on signals available at the end of each month with a one-day slippage added for trading during the first day of the next month. This simplistic rebalancing is a standard for testing the economic value of factors and is not optimal. Transaction costs are disregarded at this stage because they depend heavily on the value of assets under strategy management. The long-term volatility of the PnL for positions across all currency areas has been set to 10% annualized for presentational purposes.

Positions in individual sovereign CDS are adjusted for volatility based on a past exponential moving average of returns with 11-day half-term. This means that for the purpose of trading, we related debt trend signals to volatility-targeted returns. This is necessary because of the extreme differences in CDS return volatility across countries. Without normalization, a small set of high-volatility countries would dominate the PnL.

Naïve value generation has been modest, but reasonably consistent across time, given that the PnL relies on a single highly specialized signal and ignores all other country-specific or global directional information. The naïve Sharpe ratio of a PnL based on the biweekly signal has been 0.6. The Sharpe ratio of the monthly signal has been merely 0.04. Yet both PnLs posted a negative correlation with the S&P500 returns.

The stronger value generation of the biweekly trend may indicate that time is of the essence in trading debt sustainability. Unlike other economic trends, short-term changes in debt sustainability depend critically on market conditions themselves and, hence, are more easily watched by market participants. Simply put, the information advantage plausibly wears off faster than in the case of pure macroeconomic data.

Medium-term predictor of premia

The third hypothesis draws on the characteristic of credit exposure being similar to a short-option position with limited liquidity. A common view among traders is that markets underestimate how much the world can change and that tail risk is underpriced.

Since selling protection through CDS is akin to selling an option on default and since sovereign default is a remote risk in non-crisis times one should expect that the premia earned on a short-protection CDS position are low when debt sustainability looks good or is improving. Premia should be higher when debt sustainability is challenged and has deteriorated. Hence, we would expect a positive relation between medium-term extrapolated debt ratio trends and subsequent medium-term short-protection CDS returns.

The evidence for that relation is tentative rather than conclusive. While there is indeed a positive relation between past annual and biannual debt ratio trends and subsequent (quarterly) CDS short-protection returns, it has not been significant for the full panel of cross-sections. The positive relationship has been significant only for the developed markets, ever since that market became more liquid in the late 2000s.

Also, the naïve PnL analysis (according to the same rules as in the previous section) fails to provide strong evidence of value generation of medium-term extrapolated debt as a normalized signal for CDS positions. While there has been good value generation over the past 10 years, the signal would have produced a negative PnL during the previous years of the great financial crisis and the euro area sovereign credit crisis.